Contents

Retail & Non-Retail

BBC records can be split into two groups. One group, BBC Records, a relatively small number pressed in large volumes for sale to the public (retail), and the other a vast number pressed in relatively tiny runs for use by the BBC internally or other broadcasters and studios worldwide (non-retail). BBC records, of the other kind. In this second group, there are perhaps 80,000 discs which very few people are aware even exist, compared to around 1000 for retail. Some of the retail records were huge sellers; part of the zeitgeist.

Heard But Not Seen

A small sample of the material in the non-retail catalogues was repackaged by BBC Enterprises, sound effects in particular, but plenty of historical recordings too, whilst the vast bulk of it remains in almost total obscurity. It was made to be heard, never meant to be seen or make its way out of the studios. Some of it was supposed to be disposed of after a period of time and, by rights, should not exist now.

There is no complete list of non-retail records in the public domain. I’m not sure if the BBC have such a complete catalogue either. They exist as curiosities of the record-collecting world and even after years and years of auctions and sales online, the true scale of the discography has, I suppose, till now (2023), never been researched and explained.

Private Functions

Internal, not external. Private, non-public. Functional, working records. Records with a job. For professional use only. Not for sale to the public. Either for broadcast, re-broadcast, archiving purposes or studio use. What to call these records? What catch-all name? Non-retail seems the most accurate and defines these records in relation to the more familiar retail records, from BBC Enterprises and BBC Publications. I’d prefer something catchier, perhaps more descriptive, but non-retail will have to do, for now.

Type-ography

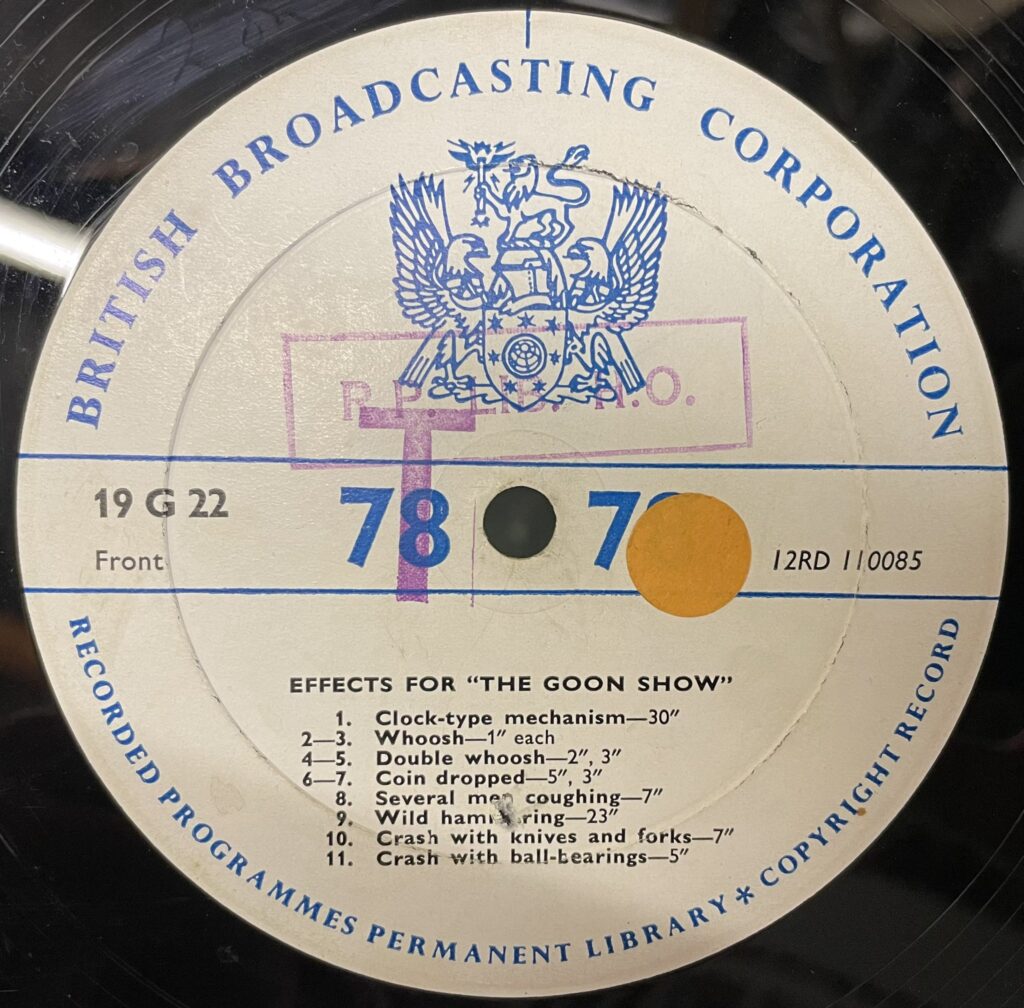

There are several types of non-retail records which the BBC created and here’s a list and a very brief summary of the ones I’ve been able to identify.

- Archive records

- Programme Library

- Transcription Services

- Sound Effects Library/Sound Effects Centre

- Radioplay Records

- Incidental Music

Archive records were a means of preserving sound. This preservation ranges from historic occasions; to famous people speechify; to eyewitnesses to momentous events to just sounds of the era. These are all moments otherwise lost to time. The Programme Library focused on retaining complete, ‘as broadcast’, programmes for rebroadcast or simply archiving. Transcription Services monetised the recorded broadcasts and also specially recorded programmes by selling them to other broadcasters. Sound effects are self-explanatory, I hope. Radioplay is the most complex to explain but was a way to workaround rules imposed by the Musicians Union. Radioplay was, in effect, an in-house BBC record label, publishing music in such a way that radio stations could fulfil so-called needle-time rules.

Incidental Music records contained music for radio use, but not as part of the music broadcast. As the labels state, this music was “Contractually available for background and incidental use only (Sect. D MU of Agreement”. I’ll come back to this another time, but the only other thing I want to add here is that I only recently saw some of these Incidental Music records and realised they existed. The list above is provisional and there may be more labels and types.

Pieces Of Tape

The first thing to state is that non-retail records pre-date their retail counterparts by several decades. Recorded sound predates the BBC, which began broadcasting in 1922, but the slightly counter-intuitive notion of recording broadcasts or saving sound for later broadcasts took some time to take hold at Broadcasting House. The remit of the Beeb was to broadcast and with the technical difficulties and frailties of recorded sound, there was not initially much importance placed on it. It was increasingly clear that the BBC needed a way to preserve important events and programmes though. In the days before magnetic recording tape was widely available this was not easy. Tape was developed into a commercial product during the 1940s after American servicemen brought home early machines from postwar Europe. Whilst that industry was developing the BBC only had one good option for keeping recordings of programmes – gramophone records. They had first aquired a Blattnerphone steel tape (edits were achieved by spot welding!) recorder in 1930/31 and began selectively transferring recordings to 78 RPM discs for later use or distribution to other radio stations – transcription discs. Recordings were also cut direct to disc for copies to be made later.

In With The Archive

Marie Slocombe deserves enormous recognition for her role in creating the BBC Archive. In 1936 she began a library of these discs, creating a sound library which included recordings in all shapes and sizes. The irony is that she was actually tasked with destroying the discs! By 1939 she and her colleagues had amassed some 2000 discs, although 10,000 “historical records” were at Broadcasting House by 1941 (according to Lynton Fletcher at the Foyles Literary luncheon, 1941). The library contained all kinds of recorded sounds in the days before the British Library took an interest.

(https://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/archive-hour–marie-slocombe-and-the-bbc-sound-archive/zvrf7nb)

The BBC’s archiving continues to this day, of course, but the use of gramophone records was gradually phased out in the 1960s. Over time tape came into use, but the expensive and somewhat fiddly machines were not widely used for a long time. Discs were preferred in broadcast studios across the world where turntables were a fixture. Whilst the archiving process went to tape, the wider non-retail record production stayed in place until CDs took over. 78s eventually gave way to Long Play (LP) 33 1/3 RPM records, which were introduced by Colombia Records in America in 1948. These microgroove discs, able to pack in more grooves and longer playing time, gradually replaced the 78s, although the BBC were not quick to make the switch. Much later digital copies were preferred and digitisation of the analogue archive continues today.

Pressing Matters

Meanwhile, discs of 12″, 16″, 10″ and 7″ sizes were produced. Pressings were made by several companies over the years. The early records seem to have come from Decca, judging by the earliest labels I’ve seen. Later HMV, EMI and others were used. The matrix codes offer clues as to who pressed what as well as the size of the disc. Some records played from the middle out. Desmond Briscoe, Organiser of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, recalls his time playing in ‘grams’ from the sound effects library for radio dramas. Having to juggle 7 or 8 discs with some playing conventionally from the outside in some from the inside outwards! The Workshop became a paragon of what tape could do, partly inspired by such experiences with disc juggling.

The first record labels

In the early 1940s (precise date TBC) the archive recordings got their own fully printed label design. Prior to that, the records had labels, but they were essentially blank forms which were then filled in by hand. The introduction of labels is not important simply for having printed details and consistent design. Nor is it just interesting for the use of catalogue numbers, although they are useful to the collector. What is significant is that with the introduction of printed labels those in charge of the pressings also began using matrix numbers. Matrix numbers and labels are inextricably linked. As well as providing a reference for the stamper the matrix number locates the label on the right side of the right disc. This is why the matrix number appears on the label.

There’s nothing unusual about the BBC using matrix numbers and nothing surprising. That they stuck with the same sequential series of matrix numbers until records were phased out in favour of CDs in the early 1990s though, is impressive. This is the BBC we’re talking about though. Anyway, it’s also rather helpful.

Catalogue & Library Numbers

Although it seems that the BBC record archive was well organised, thanks to the good governance of Marie Slocombe and her colleagues, the records they pressed didn’t follow a strict numbering system from the start. Matrix numbers were more reliable than catalogue numbering in this regard. Eventually, each type of non-retail pressing settled into its own catalogue numbering system or adopted one in due course. Not all types follow a sequence, although archive library numbers, Transcription Services ‘CN’ codes and Radioplay numbers do. Radioplay numbers are uniquely helpful because their numbers are prefixed with the year of release. Sound effects, however, use a library-style (akin to Dewey Decimal) system to categorise the effect, rather than simply adding each new addition to an ongoing sequence.

Release Dates

The most bothersome aspect of the non-retail records is the absence of, or misleading presence of, dates. Actual release dates for records are difficult to pin down, even for relatively big sellers in the retail market. The year of release is usually given by the copyright date though. Even this aspect is an issue with early BBC Radio Enterprises records, however, and much of the non-retail discs.

Before continuing, let’s just agree (or agree to differ) that non-retail records have release dates. I’m conscious of the fact that a record never published in the public domain was by definition not released in the way retail records are. Nevertheless, it’s the commonly understood term for when the record was produced and made available.

A lot of non-retail records have recording or broadcast dates printed on the label. Even without the label stating the date there are others sources of information about broadcasts (Genome) and recordings (SFX catalogues). Unfortunately, these dates do not necessarily align with the release date, although they do at least set a limit for the earliest date they could have been released. This can be misleading though and in fact, the record may have been released years later. Or even reissued decades later still. Take care when looking at dates and don’t assume someone else, on an auction site, for example, has got it right!

A lot of records don’t include any date information at all and not everything was broadcast in the UK, negating Genome. Fear not though! It’s possible to approximate the release date by taking bearings from other records. So, it’s not completely hopeless. Yes, I’m hinting at matrix numbers again, but there are other clues or sources of information which can help.

Transcription Services are peculiar in that they started including expiry dates from the mid-fifties. This date tells the subscriber when the license to rebroadcast the material has expired, and they were supposed to destroy it after that date! This expiry date is some years after the release and can be used to work back to when the record was released. If you know the expiry period, that is.

Copyright dates appeared on Transcription Services records later on and Radioplay too. The really troublesome items are in the early days and sound effects in general are very hard to date – lacking sequential cataloguing numbers and any recording dates which are known potentially decades away from when the record was issued.

Matrix Numbering

Matrix codes or numbers are used to identify the pressing, or more precisely the stamper. These exist separately from the catalogue number. Typically each side of a record has a unique matrix number, one for each stamper, even when the catalogue number is a single code. A record in the catalogue will have one number, but it can span multiple sides of several discs, each with a unique matrix number. Or, sometimes, a single-sided record. These non-retail BBC pressings came in all sorts of groupings from single-sided to multi-disc spanning volumes.

Nearly every non-retail BBC record seems to have matrix numbers from the same series. Exceptions are some Radioplay releases which are re-pressed reissues of existing albums from other labels.

The main advantage of this continuing sequence to collectors is that – and here I finally get to the point – it allows the release date to be approximated without any other date information. By cross-referencing multiple records which seem to be from the same year against their matrix numbers and those of the years before and afterwards a complete picture can be formed.

This is much easier in the years when Radioplay Records were operating catalogue numbers with the year and when TS discs had copyright dates. To make this trick work though, sufficient numbers of records are needed in all years from about 1940 onwards.

Usually, the first side has the lower of two matrix numbers with side 2 being the next number in the sequence. I would not be surprised to find exceptions to this rule though. There’s no rule as to which sides are odd or even. As already noted there were one-sided records which break so even if a run of two-sided records established an odd/even or even/odd pattern it could be interrupted. Test pressings were made one-sided and it’s possible some were rejected and new matrix numbers assigned breaking both the sequence and the odd/even rules.

Another quirk is that some records, particularly TS, where multiple discs were needed to complete the programme, did not even have sequential sides. For example, a two-disc set could have a disc with sides 1 & 3, and the other with 2 & 4. As you might have guessed, this allowed for all sides to be played back-to-back, without interruption, using two turntables. Or, they could have been stacked on a record changer, perhaps.

Old Curiosities Shopping

By now you’re probably itching to go and find out the year when all your non-retail records are actually released. Well, I haven’t quite finished my ready-reckoner yet, so, sorry, but you’ll just have to wait. You don’t have any of these precious curios? Well, I’m not surprised. Despite collecting retail BBC Records for a couple of decades I’ve only seen a couple in charity and second-hand shops over the years. Because they were never sold into shops they never accumulated in people’s homes and thence to charity shops, car-boot sale, house clearances and however else dealers get their black gold. The first I ever saw of them was when a shop I was friendly with took a load of records being offloaded by BBC Radio Leeds. I took home a few Radioplay LPs and had to reluctantly pass on a box of sound effects 7” singles. So, they leaked out of studios as they dumped their vinyl or closed down. My overwhelming donation of sound effects singles came through this route. I saw a similarly large set of SFX being auctioned off when BBC Wales moved out of their old studios.

Supply & Demand

By these various clearouts from studios whatever had not already been scrapped was saved and sold on (or kindly donated). This brings us to today’s market value. Bearing in mind that no one has good data on how many of each record was pressed, save that it was a small number by normal record’s standards, and that there’s even less idea how many survived the vagaries of studio libraries and their retention policies, and that even if quite a few are in existence they appear at random and without explanation… well, how much do you think such a rarity should be worth? We don’t even know much about how much they cost at the time of production

Clearly, the first criterion should be what is actually on the record. Is it of interest to a large number of people today? Or is it a hum-drum radio programme that was only modestly interesting in 1956, let alone in the 21st century? Is it a unique or at least rare recording, perhaps? Or just something already easily available via retail releases. Often the most prized stuff has already been reissued. That live concert recording that fans taped off the radio in the seventies and passed around copies of in the 80s (or bootlegged) is now a CD from the 90s available on a streaming service today. Still, a true collector would want the original TS LP – it’s on vinyl, after all. No surprise then that these kinds of relics can fetch astronomical sums.

The more questionable result of this uncertainty is that even the least fascinating TS records, dullest Radioplay LPs and most annoying sound effects records are all offered for sale at relatively high prices. In many ways, these BBC records should be similar to the second-hand library music market. Both share the same odd and rare cachet but the Beeb gear is fetching a premium.

Summing Up

As noted above, I still have to find enough examples of non-retail records with good release date information to build up a ready-reckoner for transforming any matrix number into a release date. Once that is done I aim to have a tool online to make that a cinch.

I have no illusions or intentions of cataloguing all the non-retail records either. Unless the BBC can magic up such a list I will never be able to catch ’em all. What I can do is get into more detail on each type. I have a lot more information on the sound effects than I used to and hope to get even more in due course. More and more non-retail records of all types are coming onto the market each year, so who knows what else will turn up?

References

- Marie Slocombe

- Marie Slocombe 1912-1995

- Blattnerphone acquired by the BBC 1931

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/hnj413KZQx2FKn6nCLnUJA

- http://www.orbem.co.uk/tapes/blattner.htm

- Introduction of LPs

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/foyles-literary-luncheon–the-bbc-recorded-programmes-department/z72kf4j

- BBC Transcription Services

- The BBC Radiophonic Workshop – The First Twenty-Five Years (BBC, Briscoe, Desmond; Curtis-Bramwell, Roy, 1983)

- https://www.recordedchurchmusic.org/radio-broadcasts